Coding on Paper with Tivadar Danka

Tom: Coding on Paper

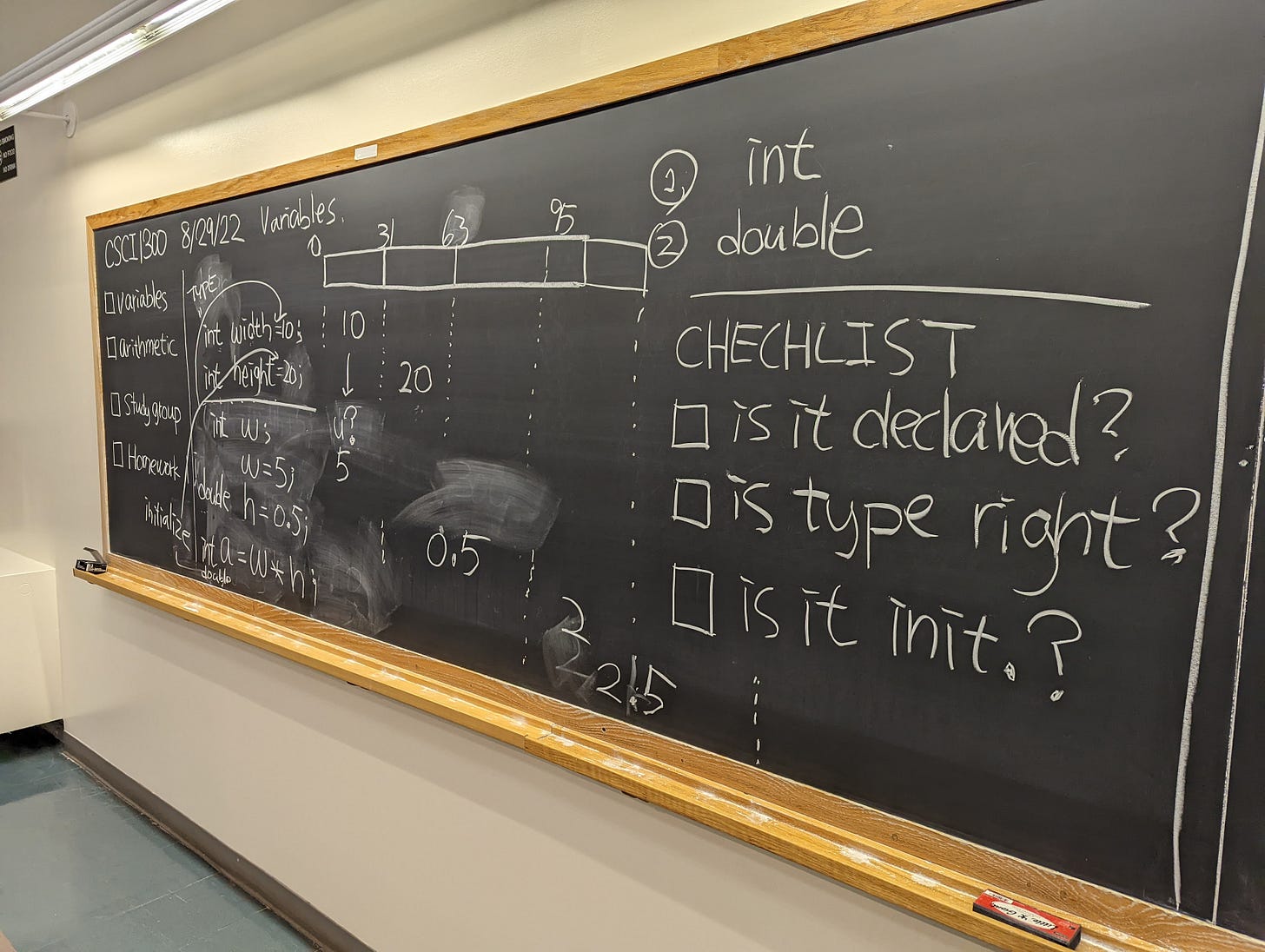

ChatGPT forces many professors to give coding assignments and exams on paper to deter cheating. Before ChatGPT, I was one of the few faculty in my department who consciously chose to teach the freshman Introduction to Programming course this way. While others preferred live coding, I taught entirely on the blackboard and asked my students to write code on paper—just as I wrote it on the board.

It’s not because I am anti-technology. It’s because I believe coding on paper has many benefits: it slows you down, forces focus, and makes your thinking visible. You can’t rely on autocomplete or a compiler to save you—you have to reason through every line.

But I always found it hard to communicate why this mattered to students.

I recently read a wonderful “coding on paper” article by Tivadar (the author of the bestseller Mathematics of Machine Learning) that describes his experience from the other side—as a student taught coding on paper by professors and as a professional taking years to gradually appreciate the value of coding on paper. I couldn’t help but wish my students could read his article.

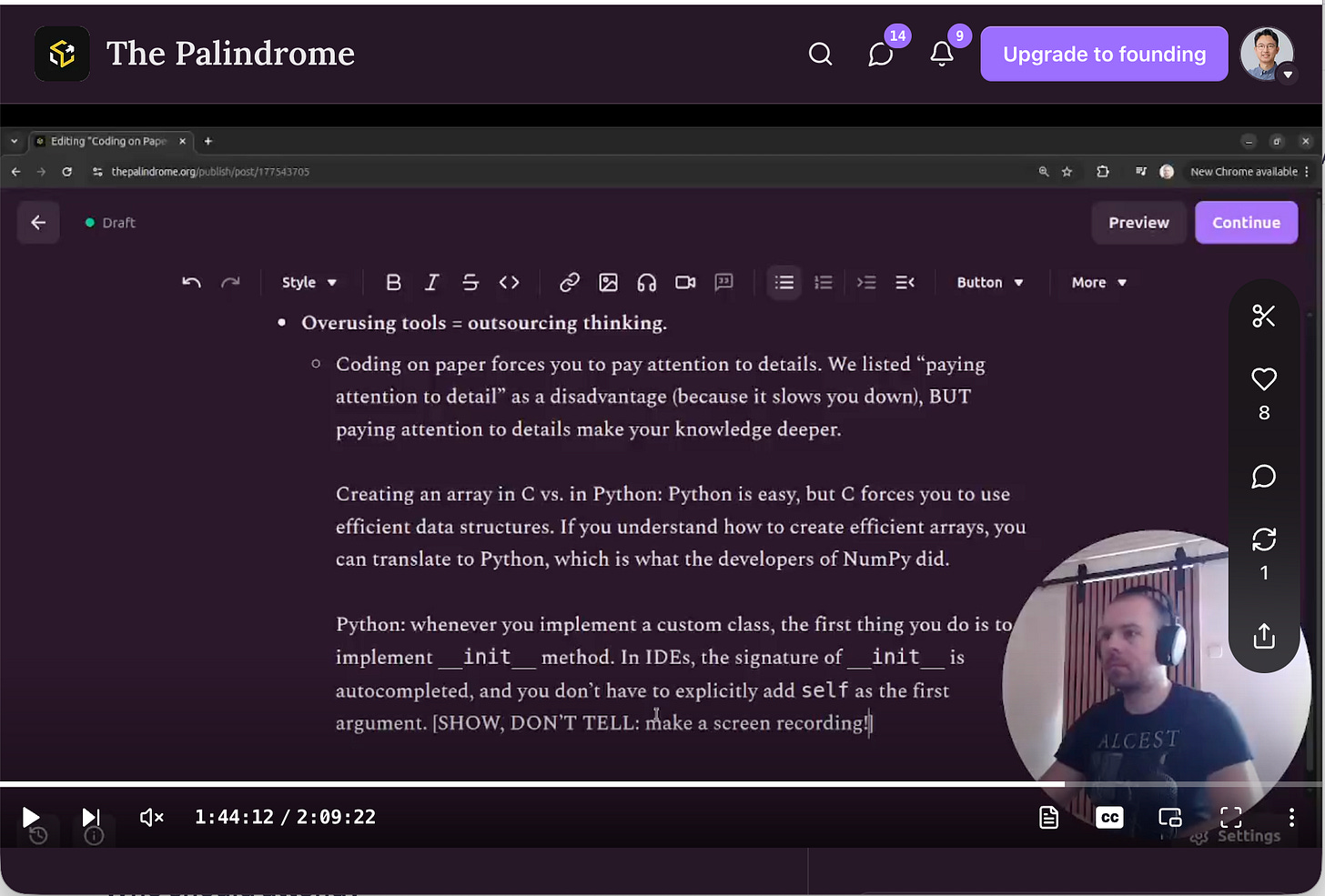

Moreover, Tivadar shared a 2-hour recording showing how he drafted his article live—just to prove that it was written entirely by a human, not by AI. The internet is now flooded with AI-generated content. It’s definitely placing burdens on creative writers like us just to cut through the noise and show that our work is not generated by AI, as well as burdens on readers like you to tell whether something that looks awesome is a genuine work by humans or a fake by AI.

I reached out to Tivadar and invited him to share the article with the readers of AI by Hand. He graciously agreed. The article is normally a paid piece from his newsletter, The Palindrome, and I highly recommend subscribing to it as well.

Next is Tivadar’s take on coding on paper:

Tivadar: Coding on Paper

When I was a young mathematics student, one of my first university courses was “Introduction to Programming,” where the computer scientists in our faculty threw us, innocent and naive mathematicians, straight into the deep water.

In the Eastern school system, we believe in immediately applying pressure so intense that it weeds out the unworthy faster than they can chug their welcome drinks at the regular semester launch parties. So, fifteen minutes into the first lecture, we were dereferencing pointers left and right, because everything else was trivial. At least, according to our professor. (By the way, this was the same in our math courses. The first sentence of our linear algebra class was “let F be a field, then V is a vector space over F if…,” leaving our heads spinning.)

I remember having classmates so technologically inept that they could hardly manage to navigate in Windows XP (the most popular OS at the time), let alone compile C code. So, the “Introduction” to Programming class felt like a punishment for most of us.

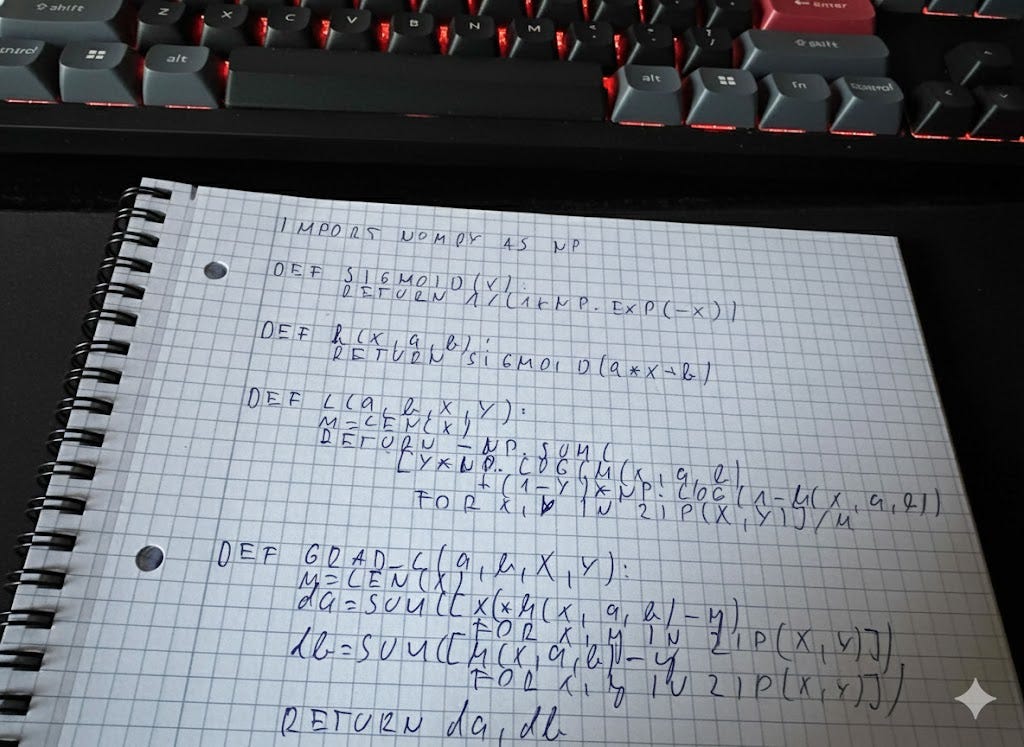

The pinnacles of our gauntlet were the coding on paper exercises, where we had to write functioning C programs — with pen and paper.

Coding on paper is antithetical to how we code in practice. Whenever I’m working on a project, I never progress linearly. I constantly change implementations, refactor, bugfix.

Nowadays, I write most of my code in Jupyter Notebooks, where

I take a shot at implementing the function,

test it on a couple of examples,

and fix all the dumb mistakes I’ve made, perhaps even prompting an LLM or two meanwhile. (Or Googling when I feel old school.)

None of that is available on paper. No autocomplete, no syntax checks, no code formatter.

With pen and paper,

you can’t run the script,

you don’t have autocomplete,

and you can’t change the “code” you’ve written.

It’s linear, uninteractive, and tedious. Coding on paper felt like a punishment.

Is there a point?

I used to believe there wasn’t; now I know there is.

The revelation finally came by drawing analogies, my Number One Tool for observing patterns. Patterns that might be hard to observe in our objects of study, but obvious when looking at analogies.

(Sometimes, we are emotionally charged, like I am about coding on paper, which I used to hate. However, taking another perspective through analogies can help us see clearly.)

How about having an LLM write your essay for you?

Even when generative AI is allowed, you cheat yourself by outsourcing cognition to a language model. The purpose of writing lies not only in the final outcome, ready to transfer your thoughts to other minds, but in forming those thoughts as well!

What is writing? As said by Donald M. Murray in his famous essay “Teach Writing as a Process Not Product”, writing is

“…the process of discovery through language. It is the process of exploration of what we know and what we feel about what we know through language. It is the process of using language to learn about our world, to evaluate what we learn about our world, to communicate what we learn about our world.” — Donald M. Murray

Coding — that is, engineering and building systems — is also a process, not just a product.

Here’s the catch: you can only get better at delivering products if you master the process. There are no shortcuts.

“But Tivadar, how to master the process?”, you might ask.

By practice. Lots of practice. And by far the best way to practice is to restrict your tools. To make it as hard as possible.

Have you ever seen an athlete exercise with a mask that limits airflow? Something like this one:

That’s just to make things hard, to help them perform even better when the restriction is lifted.

When I was practicing Kung Fu, our trainer instructed us to practice complex moves with our non-dominant hands. This technique is magic: after stumbling around with a wooden stick in my left hand for a couple of minutes, I could effortlessly perform the flashy movements with my right hand. (I’m right-handed.)

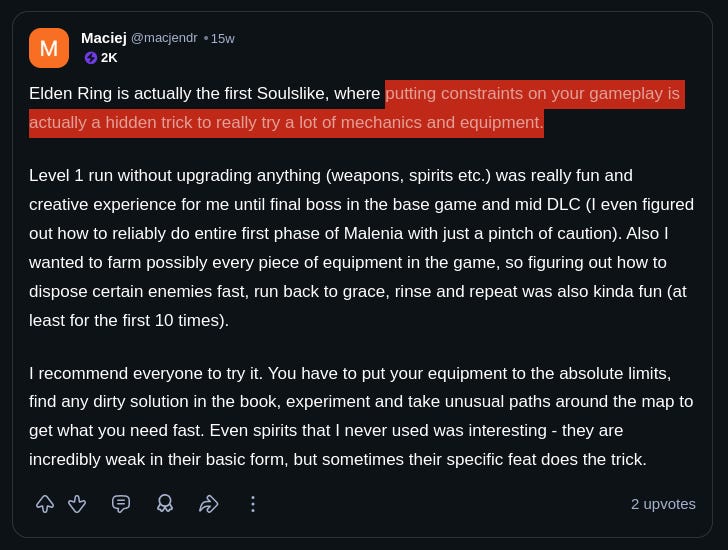

Another example: a couple of weeks ago, I wrote about the life lessons that Elden Ring, a particularly difficult video game, taught me. One comment was talking about the air-restriction-training analogue for Elden Ring: “putting constraints on your gameplay is actually a hidden trick to really try a lot of mechanics and equipment.”

By purposefully denying yourself, say, wearing armor, you are forced to get good at reading attack patterns and dodging at the perfect moments. When any boss can one-shot you, there’s no room for error.

Another example (the last one): I want to move towards video content and live lectures, so I started live-streaming a lot on Substack. (This very post was drafted live.)

Going live puts a metric ton of pressure on me, and I already feel my discipline snapping into place. I’m focused on work, prepared for the lectures, and my spoken English is already better.

That’s when I realized that coding on paper fits the above. It took me a decade and a half, but I’m finally there.

Coding on paper forces us

to pay attention to details (instead of letting autocomplete do it for you),

to be deliberate (instead of brute forcing our way to a solution through trial and error),

to figure things out on our own (instead of outsourcing our cognitive abilities to an LLM).

Whenever you are alone with a pen and a piece of paper, there’s room for your thoughts.

Now, I know that by restricting our tools, we can build the muscles whose work we offload to tools.

Muscles that will carry all the cognitive load for you later.

Tom

After reading Trivadar’s article, I’ve found a renewed sense of energy as I think about returning to the classroom to teach my students.

If you’re interested in significantly upskilling your mathematics training, here’s a great opportunity. On January 24, Trivadar will be running a 4-hour live workshop on the applied mathematics behind machine learning.

Here’s the link to check it out:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/applied-mathematics-of-machine-learning-tickets-1974977873986?aff=Tom

Trivadar generously shared a special 40% off coupon for AI by Hand readers: TOM40

I’m not receiving any commission—I simply think this could be a valuable opportunity for some of you.

Let me add a few more reasons.

1. Static analysis and ownership. Almost nobody talks about this. When you write by hand, you know right away if the code you are reading will compile and work. You can catch the errors and typos long before the compiler. This leads to attention to detail. You also learn to read the code and start wondering why some parts cannot be just cut out. You then realize that you did not think about the edge cases. This is where using an LLM to write the first cut is outright dangerous. Using an LLM once you are ready (and before running against tests -- we are still in static regime), exposes your blindspots.

2. Writing by hand makes you curious about the design decisions. Try to write a template with move and copy constructors with noexcept and pretty soon you will realize that you do not understand how things work.

3. Writing by hand creates a recall. Recall involves observing patterns from naming to understanding the authors themselves. You can then predict what a method name will look like when you are in a new part of the language.

4. Slowing down also makes you wonder how a certain function was implemented. Numpy deserves a mention here because of broadcasting and other shortcuts. I will bet you that most people do not understand what those access by row, column, or any other axis in a tensor mean, so they cannot write the code with pen and paper.

5. To build on your attention to detail: Example: in binary search, when does one use while(low < high) vs while(low <= high).

Eventually, you learn to read the code as if it were a novel and without any comments and any other crutch. This is the owning part.